Model Selection and Evaluation

The model was trained using 60% of the ~53,000 row dataset. 25% of the data was used for calibration and validation, retaining the remaining 15% of the data as a test set.

Model Selection

The team experimented with numerous models of various complexity, starting with a simple logistic regression model, which served as a parsimonious baseline against which other models could be compared.

The next model attempted was an Extreme Gradient Boost (XG Boost or XGB) model, an implementation of gradient boosted decision trees known to work particularly well for the relatively small-sized, dense data used in this project.

Finally, to experiment with a completely different family of models, the team constructed a simple neural network.

All three of these initial models were “uncalibrated”, with XG Boost performing considerably better than the other two (see Model Evaluation subsection below for our evaluation criteria). To further improve

model performance, models were run through a calibrated classifier, which is specifically designed to improve the quality of the models' predicted probabilities. This resulted in three additional calibrated versions of the models, all of which performed slightly better than the uncalibrated XG Boost model, and which were all similar in performance.

Ordinarily, "black box" models such as XG Boost and neural networks have the undesirable tradeoff of sacrificing interpretability for performance. However, the use of Shapley values (see Shapley values section below) to communicate personalized

feature importance enables physicians to interpret which features increase or decrease a patient’s risk score, something the team deemed vital for tool usefulness and adoption.

Model Evaluation

Brier Loss Score was the primary evaluation metric used to assess model performance. Though perhaps not as well-known as other evaluation metrics for binary classification, it has been used since 1950.

Brier Loss Score is a practical method for this use case because it is specifically designed for probability evaluation. For example, in a group of 100 patients, all of whom have a predicted probability of approximately

20%, Brier Loss Score will indicate the best performance when 20 of those patients actually misused opioids and 80 did not. It is important to remember, unlike is often the case of binary classification problems, the goal

of this project is to predict the probability of opioid misuse rather than the binary outcome of a patient misusing or not misusing opioids. Therefore, traditional model evaluation techniques such as Precision, Recall,

F1 Score, and ROC AUC metrics were not helpful in evaluating desired probability outputs, as they focus on ratios of false positives and false negatives as opposed to measuring probability.

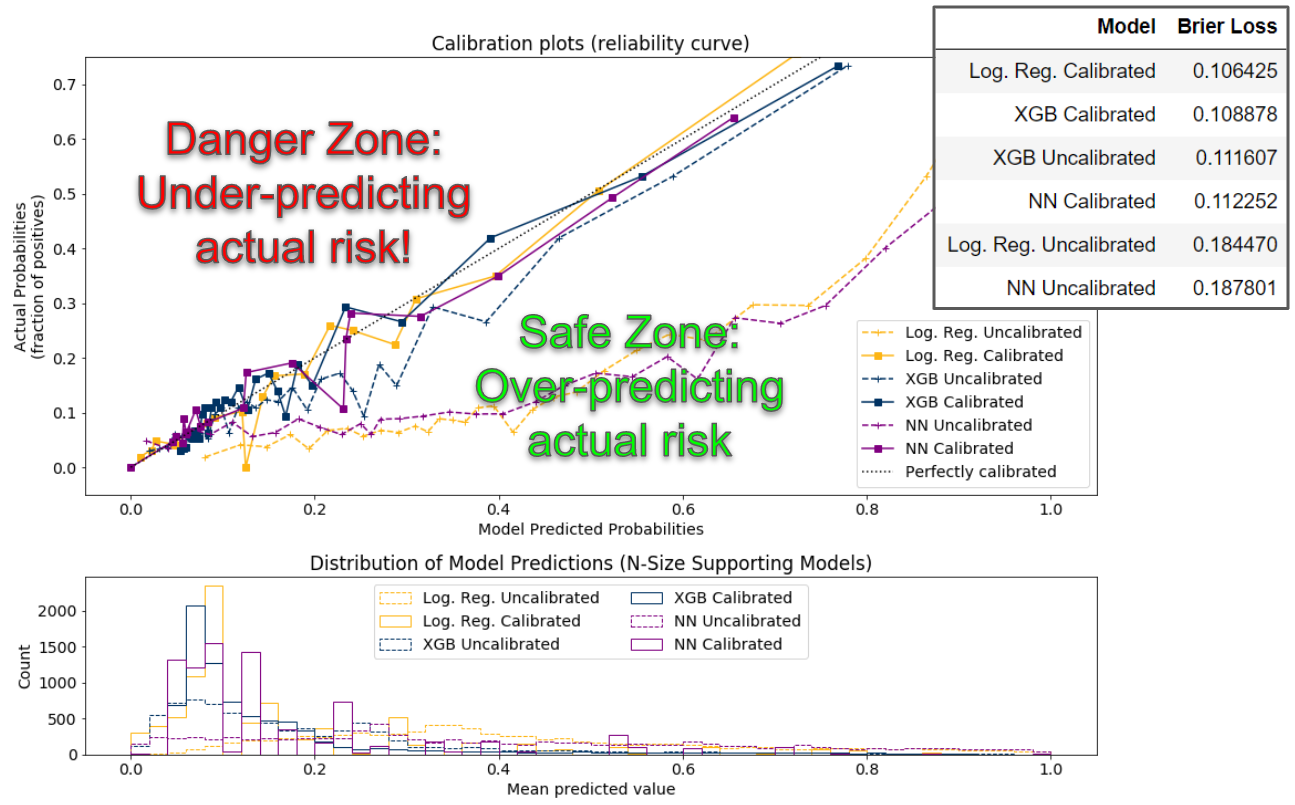

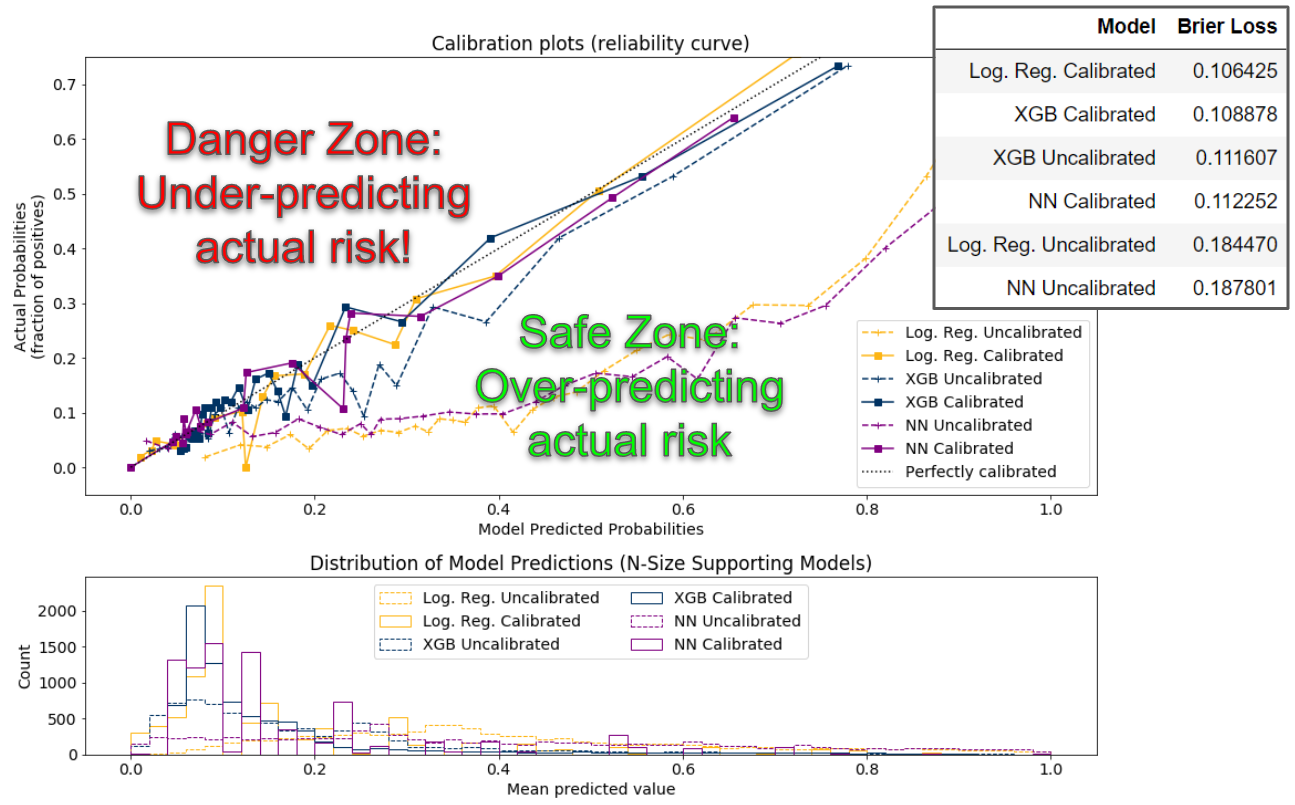

The team also generated calibration curves (a.k.a., reliability diagrams) from the test data for each model, which compare the relative frequency of what was observed to the predicted probability frequency.

While the best models are closest to the diagonal line, which represents a perfectly calibrated model (each probability predicted by the model is exactly correct), since no model is perfect, the team preferred models

whose bias overestimated risk (the safe zone) rather than underestimated risk (the danger zone). The diagram below depicts model performance on these calibration curves.

In all the top performing models (those closest to the diagonal line), even at their worst performance, the predicted probabilities are only roughly seven percentage points away from the actual probabilities,

a good practical validation of model performance.

Additionally, the histogram shown below the calibration plot shows a similar distribution among the calibrated models, with most patients scoring between 0% and 20% likelihood of opioid misuse, and the long right tail showing few people scoring higher.

Final Model

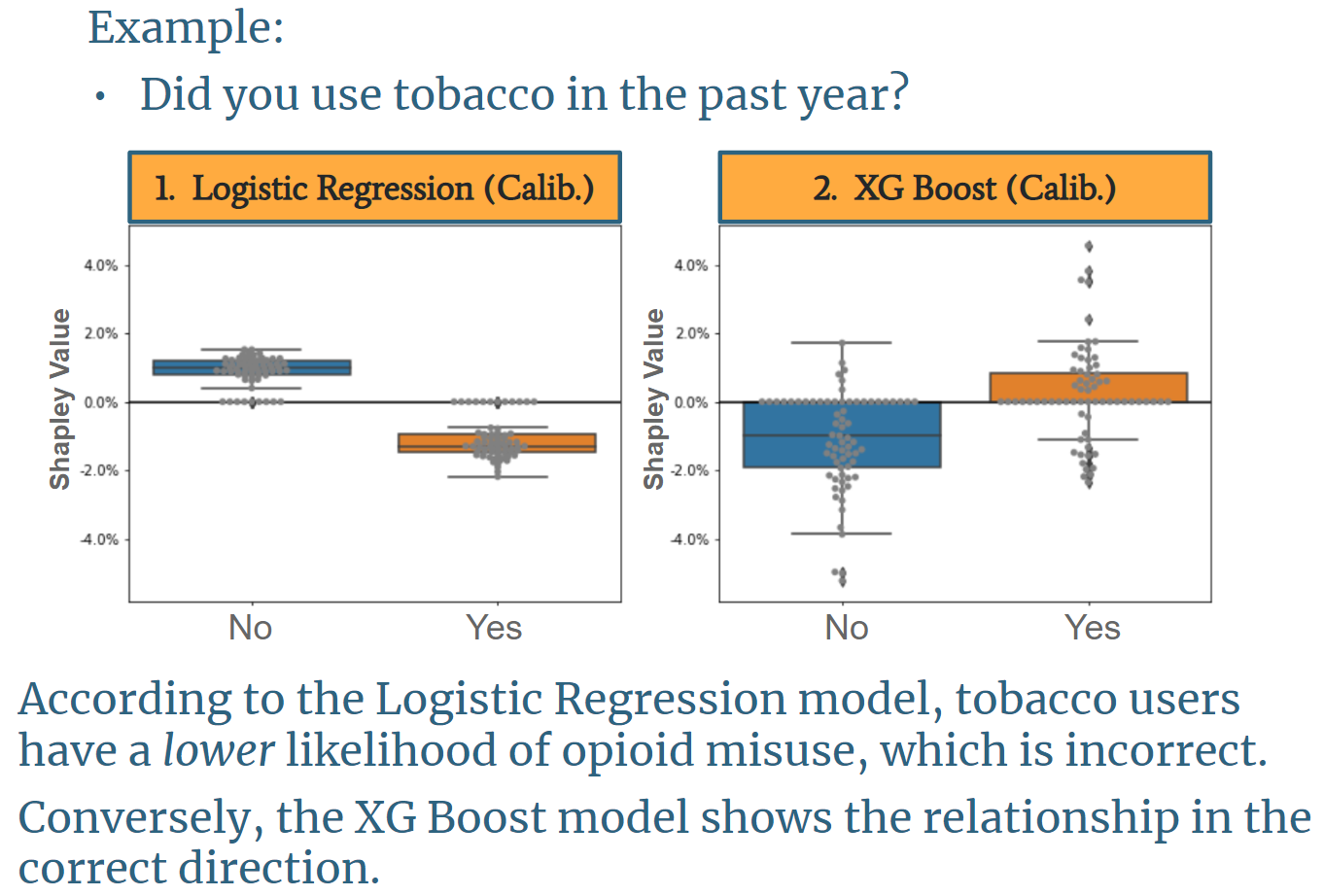

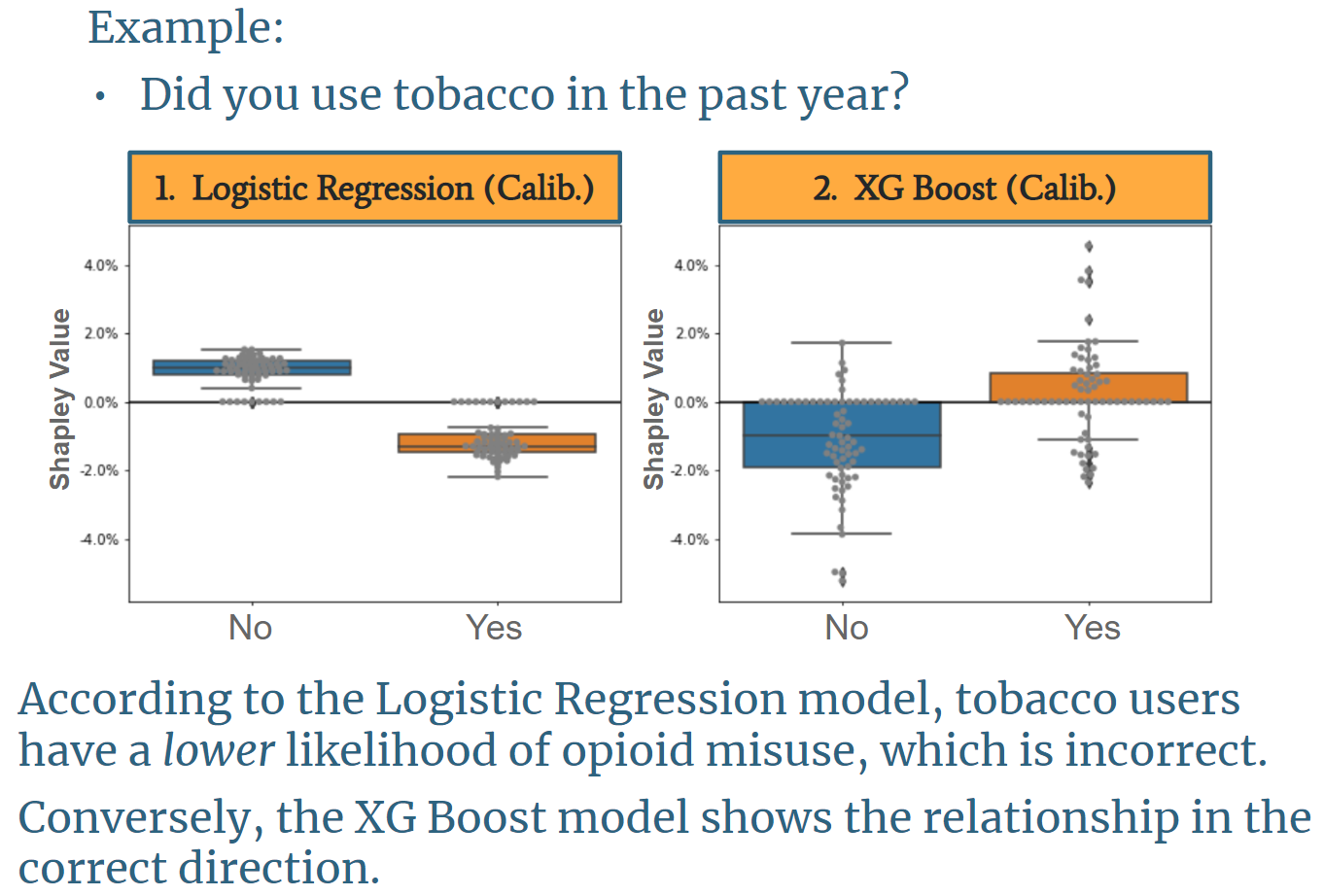

The final model chosen for the OMR Tool is a calibrated XG Boost model. While the calibrated logistic regression model had a slightly lower Brier Loss Score, the team ultimately chose the calibrated XG Boost model

because it incorporates feature interaction, making the personalized feature importance output (see Shapley Value section below) far more aligned with existing literature. An example of the distribution of feature

importance of the calibrated Logistic Regression model compared to the calibrated XG Boost model is shown below.

The image above is based on a question asking if a user has smoked tobacco in the past year. It shows with logistic regression, tobacco users are less likely to misuse opioids, and non-tobacco users are more likely to misuse opioids. This finding is counterintuitive, misaligned with existing research, and misaligned with the underlying data. Conversely, the XG Boost model shows the correct direction of impact on opioid risk.

Shapley Values

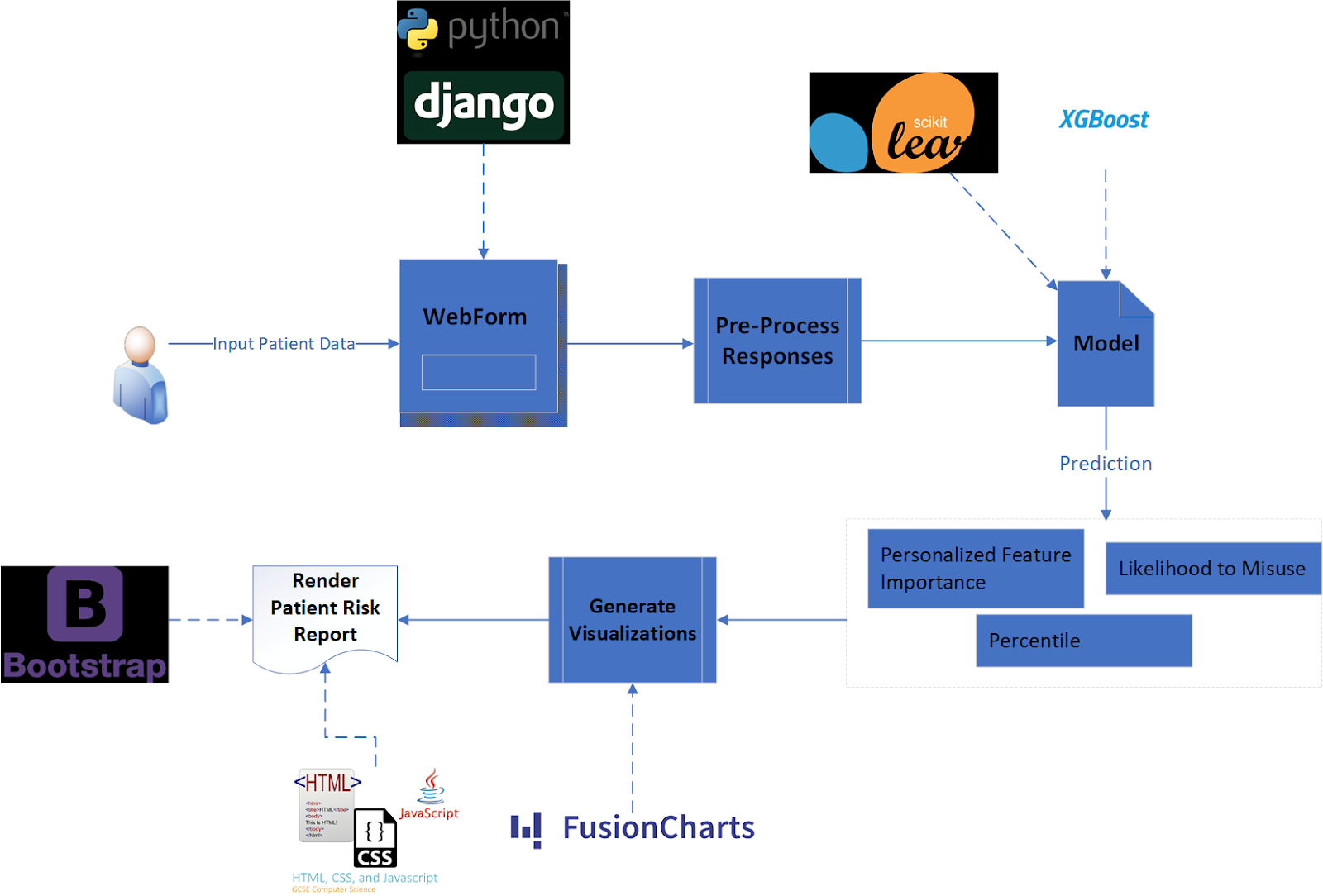

It is important for a physician to know why each patient receives their particular risk score. While this task is a straightforward output for a simple uncalibrated logistic regression model, as model complexity increases,

human understanding of the model typically decreases. To add clarity for our users and to help physicians understand the risk for each of their patients individually, the OMR-Tool provides a visual output of each user’s top

five features (i.e., patient answers to each question) that contributed most to their total risk score, displayed as a two-sided bar graph. A Shapley value shows how much each feature contributes to the overall

risk score. Mathematically, a Shapley value is the average marginal contribution of a feature value across all possible combinations of features from our model. For one patient, their previous non-opioid substance abuse may have

been the primary feature that brought their risk score up, but for another patient, even if they also have the same history of non-opioid substance abuse, it could be the simple fact of, for example, being young and male that

contributed most to their individual risk. Each patient is different, and the tool assesses each individual’s information holistically, rather than statically question by question as in previous risk assessment tools.

It is important to note, however, that this tool does not claim experimental causality between the features and opioid misuse; rather, it is claiming predictive association between the features and opioid misuse.

For example, it would be technically incorrect to say that being young and male causes a patient’s risk score to go up, but it is acceptable to say that being young and male is predictive of and/or contributes to a patient’s high risk score.

While achieving causal proof of the relationship between features and opioid misuse is ideal, the experiment required to achieve this claim is infeasible for many reasons. Moreover, there is a long precedent in the medical world

to use predictive association, as illustrated when a physician asks if a patient has a family history of some condition. While family history can be predictive of a condition, it doesn’t mean that it has been causally proven to drive that

same condition, yet physicians frequently use it as an indicator of patient risk for that condition.